When the Environmental Law Institute (ELI), with funding from the EPA, set out to conduct a comprehensive review of state wetland protections in 2005-2007, they undertook a complex task.

Protecting wetlands from pollution and degradation is generally considered to fall under the Clean Water Act (CWA), [1] but the way individual states apply or build upon that base evolved separately influenced by their geography, history, circumstances, and populace. Wetlands may also receive regulatory protection under federal, state, and/or local laws. [2]

Additionally, the timeframe of ELI’s study spanned what might be called a watershed moment in wetland protections law and regulations: Rapanos vs. the United States (2006), a case that hinged on the definition of wetlands; the Supreme Court was unable to come to a majority decision and instead issued five separate opinions.

In the wake of Rapanos vs. the US, the bodies of water that fall under the jurisdiction of the CWA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are commonly interpreted to include: (1) traditional navigable waters (TNW); (2) wetlands adjacent to TNW; (3) non-navigable tributaries of TNW that are relatively permanent (where the flow is year round or is seasonal, typically lasting three or more months); or (4) wetlands that directly abut such tributaries. [3]

In 2008 the EPA issued a new rule to [improve and consolidate] existing regulations and guidance, to establish equivalent standards for all types of mitigation under the Clean Water Act Section 404 regulatory program. [4]

Table of Contents

Section 401 Gives States Wetland Authority

The Clean Water Act section 401 gives state agencies the authority to evaluate projects and issue permits certifying that a given project won’t result in disturbances or discharges that diminish water quality below state-set standards.

States may apply section 401 for only some parts of the state; for example, multiple coastal states use their own state-established permit programs for coastal wetlands but utilize section 401 to regulate inland wetlands.

Certification decisions under 401 may be made using either quantitative or qualitative methodology, but generally speaking are applied according to responsible staff’s best professional judgment (see State Wetland Program Evaluation (SWPE) Phase I, Figure Four). [5]

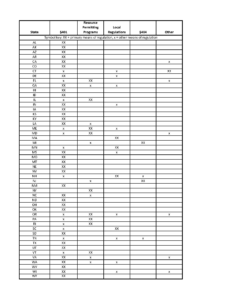

For 22 states, section 401 of the Clean Water Act is the primary means of regulating wetlands activities. The other 28 states may rely on local regulations, section 404 of the CWA, or non-regulatory methods, or on a combination of these types of regulations (see Table 1).

Section 404

Under section 404, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has authority to issue permits having to do with discharge of fill material into US waters, including wetlands adjacent to navigable waters. [6]

Michigan and New Jersey have assumed section 404 permitting duties from the USACE – the only states to have done so, and both rely primarily on it for wetlands protections (although ?401 still applies in interstate waters).

Michigan was the first state to assume responsibility for applying section 404, in 1984 (SWPE Phase I, pg. 67). The USACE still has jurisdiction over traditionally navigable waters in Michigan, i.e. the Great Lakes, and their adjacent wetlands; the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality has jurisdiction over other state waters (and local governments generally have jurisdiction over small wetlands of less than 5 acres).

New Jersey took over section 404 permitting authority in 1994. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is responsible for administering permits. In addition, New Jersey applies special sets of laws to various unique regions within the state: the Freshwater Wetlands Protection Act, the Wetland Act of 1970 (for coastal wetlands), the Pinelands Protection Act, the Hackensack Meadowlands Reclamation and Development Act, and the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act (SWPE Phase 2, pg. 64).

Connecticut does not primarily rely on either section 401 or 404. Instead, it has separate and complimentary regulatory programs for inland and for tidal wetlands: inland wetlands fall under the jurisdiction of the Municipal Inland Wetland Agencies (MIWA) and are regulated at the municipal level; tidal wetlands are regulated by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection’s Office of Long Island Sound

Programs (SWPE Phase III, pg. 71).

Twenty-three states retain authority to issue permits for dredge and fill activities in wetlands. Of these, 15 regulate permitting for both freshwater and coastal wetlands, and 8 oversee only coastal wetlands (Table 1).

Regulatory State Agencies

In total, 123 state agencies across the United States are responsible for wetland regulation, management, and/or protection (SWPE Final Report, p. 32). About half of the States ? 26 in total ? divide the responsibility between two state environmental agencies: usually, one of the agencies takes care of permitting while the other oversee non-regulatory projects.

Twelve states delegate the work to a single central environmental agency: Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Michigan, Montana, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

Thirteen states have adopted additional water quality criteria and protection policies specific to wetland resources. Water-quality standards may include wetland-specific standards, chemical standards, and/or biological standards (SWPE Final Report, Figure 9-A).

For waters that are not covered under section 401 or 404; eg, intermittent wetlands and streams that contain water only part of the year, or marshland that is not adjacent to open water, some states have established additional laws (SWPE Final Report; see pg 61).

Wisconsin was the first state to pass legislation to expand its powers to protect wetlands beyond the purview granted by the CWA. [7] In 2001 the Supreme Court heard the case Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (SWANCC) v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and ruled to limit the CWA’s application to isolated wetlands (in particular, they ruled that federal protection should not extend to isolated wetlands solely based on the wetland use by migratory birds). In response, 2001 Wisconsin Act 6 expanded the state’s protection over isolated wetlands, protecting over one million acres of isolated wetland from which federal protection had been withdrawn. [8]

Washington State also adopted a state-level definition of wetlands that includes the isolated wetlands not under ?401/?404 purview, and protects the through water quality rules, permitting, and administrative orders. [9]

Vermont?s state-level regulatory approach categorizes and extends protection over wetlands that ?provide significant functions and values [or provide] a buffer zone directly adjacent to significant wetlands? ? wetlands Vermont classifies as protected include places of irreplaceable natural heritage, and amphibian breeding habitat. [10]

Conclusion

Regulating impacts to wetlands is a varied and process throughout the U.S. Familiarity with each State’s regulatory programs or at least with the specific networks of regulations particular to your area of interest is vital to navigate the complexities of definitions and responsible agencies.

In the years since the 2008 publication of the State Wetland Program Evaluation summary, the ELI has continued to publish studies and guidance, including the Clean Water Act Jurisdictional Handbook, 2nd Edition (2012) and a 2017 webinar on Developing Wetland Restoration Priorities for Climate Risk Reduction and Resilience. [11]

Disclaimer: This article is a brief intro / summary, not to be used as legal advice. Always retain and consult a qualified professional for your specific project.